In the spring of 2015, after having submitted my phd thesis, I attended an applied microeconometics course at the University of Oslo given by Monique de Haan, Tarjei Havnes and Edwin Leuven. I have previously blogged about a paper using the synthetic control method that grew directly out of that course. Now a second paper originating in a presentation in that course has been published: “Distributional effects of welfare reform for young adults: An unconditional quantile regression approach,” Labour Economics, Volume 65, August 2020. The article is open access.

In the quantile regression class, I presented the paper “Is universal child care leveling the playing field?” by Havnes og Mogstad (Journal of Public Economics, Volume 127, July 2015). That paper uses several non-linear differences-in-differences methods to study the distributional effects of child care. One of their applied methods was the unconditional quantile regression approach of Firpo, Fortin and Lemieux (2009). At the time, I was working on the topic of welfare reform in Norway, and I realized that I could apply the same method to that question. That started a journey that now, 5 years later, has resulted in a published paper.

In the paper, I analyze what happened to earnings when Norwegian municipalities increased their use of conditions for (primarily young) welfare recipients. Of the age group I analyze in the paper (26–30 year olds), 8% received welfare at some time in 1993, the first year of the analysis. Welfare policy affects both those actually receiving welfare as well as a wider population with only a potential connection to the welfare system. I do not know exactly who is impacted, but the fact that changes in welfare policy mainly affect people with a low earning potential suggests going beyond the mean impact and analyzing the effects on the distribution. It is likely that the relatively small average effects mask an effect of higher earnings among low earners and no effects among high earners.

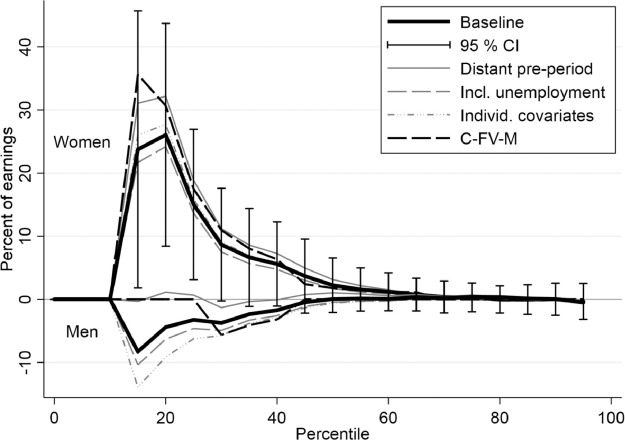

What do I find? Substantial positive effects of increased use of conditions in parts of the lower end of the earnings distribution for women and no or small negative effects for men. For women, earnings at the 20th percentile increase by around 25 percent, or € 2000 per year. As expected, there are no effects in the upper part of the distribution. Below is the key graph:

Fig. 3. Main quantile treatment effect estimates on earnings, 26–30 year olds.

Further, I find that although welfare payments decline, the effect on total income for women is also positive, indicating that they were able to find gainful employment that, overall, improved their financial circumstances.

I conclude that it is important to mention that the reform occurred in a beneficial environment, which may help to explain the good results. First, the reforming municipalities were responsible for undertaking and implementing the changes and therefore likely had a large degree of ownership of the reform and a strategy for implementing it. This may be hard to replicate in the case of changes mandated from a higher authority. Second, the social insurance offices had a large degree of discretion in deciding who should face conditions and what to demand of them. This may be beneficial compared to uniform requirements if caseworkers have relevant information about how to adapt the conditionality policy. Nevertheless, the policy represents a promising avenue to explore for other countries in need of social insurance system reform.